There are arguably few things more quintessentially French than the humble baguette, underscored by the stats that almost six billion are consumed each year.

However, it’s not the bread alone that has been officially recognised – but the ‘artisanal know-how and culture of the baguette’, defined by the UN’s cultural body as “traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants”.

Specific knowledge and techniques

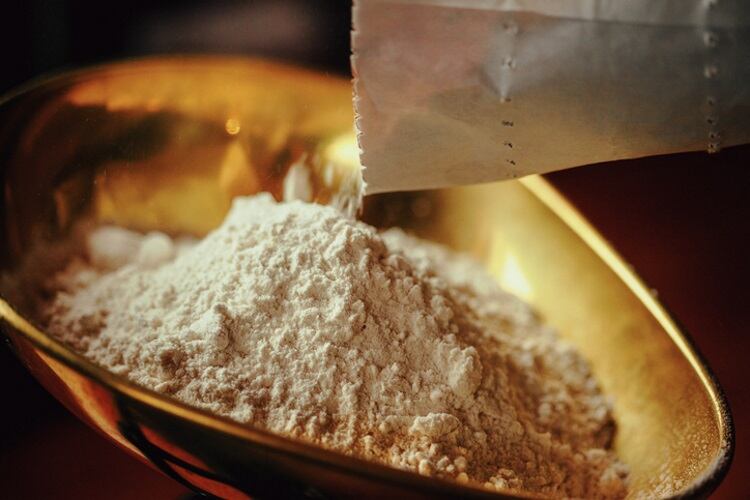

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), “the traditional production process entails weighing and mixing the ingredients, kneading, fermentation, dividing, relaxing, manually shaping, second fermentation, marking the dough with shallow cuts (the baker’s signature) and baking.”

Making the baguette – which means ‘wand’ or ‘baton’ – requires “specific knowledge and techniques: they are baked throughout the day in small batches and the outcomes vary according to the temperature and humidity.”

Added Unesco, “They also generate modes of consumption and social practices that differentiate them from other types of bread, such as daily visits to bakeries to purchase the loaves and specific display racks to match their long shape.

“Their crisp crust and chewy texture result in a specific sensory experience.”

250g of magic

The move confirms what French president Emmanuel Macron has long been touting. A key advocate in getting it added to the list, Macron says the baguette is the “envy around the world” and is “250 grams of magic and perfection in our daily lives."

The exact provenance of the baguette is highly contested.

Some suggest it was created by Austrian officer-turned-baker August Zang in the 1839s (Zang also purportedly introduced Paris to the pain viennois and croissant), while another famous origin touts earlier origins, back to Napoleon Bonaparte, who ordered a an elongated-shaped loaf that would be easier for his troops to carry.

An alternative story points to a 1920 French law, which prohibited bakers from working between 10pm to 4am, so a bread prepared and baked within 3 hours in time for bakery opening hours was devised.

But a fourth account exists, crediting the ban on workers ‘bearing knives’ on their daily commute that brought about the easy-to-tear sustenance.

However, it was that 1920 French law that essentially formed the loaf as we know it today – officially naming it the baguette; setting a standard length of 80cm and weight of 250g; and demanding that it must be baked on the premises where it is sold.

The French Bakers Confederation takes the ruling a step further, decreeing the bread must only contain flour, water, salt and year; and the dough must rest for 15-20 hours at a temperature between 4°C and 6°C. The baguette even had a fixed price until 1986.

French habits

The baguette enjoyed its heyday in the 1970s, but sadly has subsequently seen a demise.

According to the Observatoire du Pain, which tracks bread consumption and trends in France, the average daily consumption rate of bread among adults decreased from 143g/day in 2003 to 103g/day in 2016 – blamed on the rise of supermarket chains selling mass-produced, cheaper alternatives.

But with something now to celebrate, hopefully the French staple will enjoy a resurgence.

“The baguette is a daily ritual, a structuring element of the meal, synonymous with sharing and conviviality. It is important that these skills and social habits continue to exist in the future,” UNESCO chief Audrey Asoulay told the media.

The French baguette joins other culinary cultures on Unesco’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, including Neapolitan pizza, kimchi, Belgian beer, the Mediterranean diet and Arabic coffee.